Nestlé's public

relation machine exposed

This paper gives

an overview of the campaign against Nestlé and responds

to arguments Nestlé has used in the recent past in letters,

booklets and briefings.

Also see the Your

Questions Answered page and Boycott

News and the previous version

of this briefing

If you have had

any other arguments put to you by Nestlé staff or have

any questions of your own, please contact us for further information.

Contents

Last

update 21 April 2005

Nestlé

spends a fortune trying to divert criticism of its baby food marketing,

but does it tell the truth?

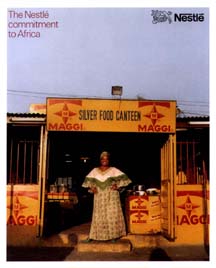

| Nestlé

has a serious image problem because of its on-going aggressive

marketing of baby foods. Instead of making changes required

to bring its practices fully into line with international

marketing standards, Nestlé invests heavily in Public

Relations (PR) initiatives intended to divert criticism. But

Nestlé makes demonstrably untrue claims which have

resulted in further damaging publicity, such as the cover

shown right. |

|

Nestlé is singled out for boycott action because independent

monitoring conducted by the International Baby Food Action Network

(IBFAN)

finds it to be the largest single source of violations of the

World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International

Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes and subsequent,

relevant World Health Assembly Resolutions worldwide. Nestlé

also takes the lead in attempting to undermine implementation of these measures by

governments (some

examples listed here - needs updating).

According to UNICEF:

"Marketing

practices that undermine breastfeeding are potentially hazardous

wherever they are pursued: in the developing world, WHO estimates

that some 1.5 million children die each year because they are

not adequately breastfed. These facts are not in dispute."

(Click

here for further details).

The introduction of

the International Code in 1981 should have ended the malpractice,

but companies continue to violate it today.

An increasing number

of governments have introduced legislation implementing the provisions

of the International Code and Resolutions (click

here for the International Code Documentation Centre's State

of the Code by Country chart - 1.5 Mbytes). Nestlé pushes

for unenforceable voluntary codes in place of laws. It even took

legal action against the Indian Government in an attempt to have

the law there revoked after the company was taken to court for

not putting warning notices in Hindi on labels (see the IBFAN

report Using

international tools to stop corporate malpractice - does it work?

for case studies of countries where implementation of the Code

and Resolutions is working and where they have been undermined).

Part of Nestlé’s

PR strategy sometimes includes claiming health campaigners are

trying to ban the sale of breastmilk substitutes. This is totally

untrue. The aim is to ensure breastmilk substitutes are marketed

appropriately. Other bogus Nestlé’s claims are exposed

below. Our position on Nestlé arises from the evidence

of malpractice. We are seeking to protect infant health and mothers’

rights. Nestlé’s claims do not stand up to scrutiny.

When the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) conducted a

two-year investigation into claims Nestlé made in an anti-boycott

advertisement, it found they could not be substantiated. Nestlé was warned

by the ASA not to repeat the claims. Yet it continues to make

similar claims in public relations materials which are not subject

to the same regulations as advertisements (click

here for details of the complaints and here

for the final ruling and here

for the Chief Executive's response).

Nestlé’s

bogus arguments exposed

Nestlé

says: The problems with the marketing of breastmilk substitutes

were resolved long ago.

The facts: IBFAN’s

latest monitoring report Breaking

the Rules, Stretching the Rules 2004 documents violations

of the International Code and Resolutions gathered in 69 countries.

As in past monitoring exercises, Nestlé was found to be

the source of more violations than any other company. This is

why it is singled out for boycott action.

|

Nestlé’s

strategy is to admit to malpractice only years in the past,

even though it denied it at the time.

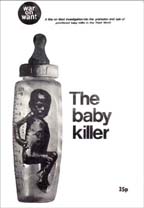

When the exposé

The Baby Killer was published in 1975, Nestlé denied

any wrong-doing. It even sued campaigners in Switzerland

who translated it into German, but had to drop nearly all

charges as experts trouped into court to provide substantiation.

Nestlé

only won against the title in German, which was ‘Nestlé

kills babies’ on the grounds it wasn’t committing

deliberate murder.

The Judge awarded

token fines and warned Nestlé to change.

|

|

Today Nestlé

admits to malpractice in the 1960s and 1970s, though it hasn’t

apologised to the families who lost infants during this period

or offered any form of compensation.

In 1999 the UK Advertising

Standards Authority ruled against Nestlé’s claim in

an anti-boycott advertisement that it did not distribute free

supplies of infant formula. Today Nestlé claims it used

to do so, but stopped in the 1990s.

Malpractice it denies

today, will likely be admitted in a few years time. But Nestlé

will say: “That was a long time ago. We have changed.”

Nestlé

says: So-called violations are not for infant formula, but

complementary foods that are not covered by the Code.

|

The facts:

IBFAN’s Breaking

the Rules monitoring report separately details violations

relating to formulas and those relating to complementary

foods.

A favoured tactic

is promotion through the health care system. This makes

it seem as if Nestlé has the endorsement of health workers. The tissue box on the

right is in the style of Nestlé’s Nan

formula labels and was distributed to health workers in

Thailand.

|

|

| Companies

are permitted to provide ‘scientific and factual’

information to health workers, but the materials Nestlé

produces on its formulas are misleading and promotional. For

example, a leaflet on Lactogen 1 claimed the formula is good

for ‘brain, body and bones’ and was dominated by

bright pictures rather than scientific information. |

|

|

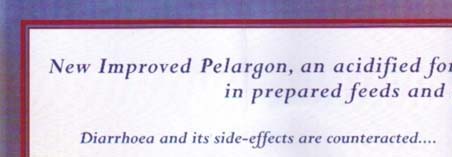

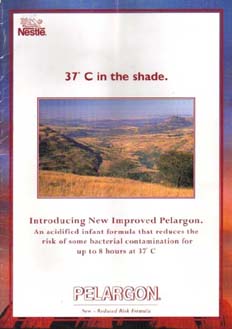

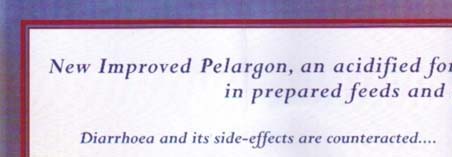

In Botswana Nestlé

has distributed a pamphlet for Pelargon infant formula

which claims that with the formula ‘diarrhoea and

its side-effects are counteracted’ (right and above

- click

for full image).

This is highly

misleading as it implies the formula can be used to treat

diarrhoea, but infants fed on Pelargon are at greater

risk of becoming ill and possibly dying as a result of diarrhoea

than breastfed infants.

|

|

|

The World Health

Assembly has also adopted Resolutions relating to complementary

foods. For example, Resolution

49.15 calls for action "to ensure that complementary

foods are not marketed for or used in ways that undermine

exclusive and sustained breast-feeding."

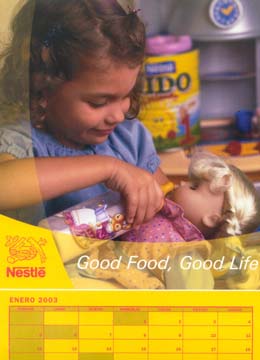

Despite this,

Nestlé promotes products such as whole milks alongside

more expensive infant formula in the infant feeding sections

of supermarkets and pharmacies (click

here for evidence). Nestlé has even produced

promotional materials such as the calendar from the Dominican

Republic on the right, which shows Nido whole milk

in a feeding bottle.

Nestlé

refuses to stop these practices even though it knows poor

mothers who have decided or been persuaded not to breastfeed

often use powdered whole milk instead of infant formula.

|

|

Nestlé

says: Isolated violations may occur because Nestlé

is a big company. Campaigners do not provide information to allow investigations.

|

The facts:

Nestlé’s own internal instructions permit violations

of the International Code and Resolutions.

The analysis

below shows some of the ways they fall short. UNICEF raised

some of these issues with Nestlé’s Chief Executive

Officer, Peter Brabeck-Letmathé in a letter in November

1997 - yet he still hasn’t brought Nestlé’s

policies into line.

Monitoring demonstrates

violations are ‘systematic’. This description

was used first not by IBFAN, but by the Inter-agency Group

on Breastfeeding Monitoring (IGBM) in its 1997 report Cracking

the Code. Then, as today, Nestlé denied any wrong-doing.

|

|

IBFAN conducts monitoring

to determine if companies are fulfilling their obligations, not

to provide a service to Nestlé.

|

The International

Code (Article

11.3) is quite clear:

“Independently

of any other measures taken for implementation of this

Code, manufacturers and distributors of products within

the scope of this Code should regard themselves as responsible

for monitoring their marketing practices according to

the principles and aim of this Code, and for taking steps

to ensure that their conduct at every level conforms to

them.”

|

|

IBFAN groups report

violations to government enforcement authorities as an on-going

activity. Many of the violations in the Breaking

the Rules report had been raised with national Nestlé

offices before it was published. Why then does Nestlé claim

it was unaware of them? Nevertheless, IBFAN provided a detailed list of where the company’s promotions had been

found to Nestlé head office when asked to do so. Nestlé

did not respond to indicate it was taking any action.

What of Mr. Brabeck’s

promise that he personally investigates any hint of a violation?

Nestlé claims

to have instigated an 'ombudsman' system, but Baby Milk Action

has written to the ombudsman asking for the violations on which

Mr. Brabeck has failed to act to be investigated and has received

no reply (click here for

details).

Nestlé

Instructions and the International Code and Resolutions. Where

do they differ?

|

The International

Code Documentation Centre (ICDC) trains policy makers on

implementing the Code and Resolutions on courses supported

by WHO and UNICEF.

ICDC’s legal

expert has compared the Nestlé Instructions (on implementing

the Code) to the provisions of the International Code and

Resolutions, and has found a dozen examples of how the company

misrepresents them to justify continued promotion (click

here for the full analysis - pdf).

The flawed Nestlé

Instructions are used by the auditors Nestlé commissions

to verify its activities (such as Bureau Veritas) rather

than the Code and Resolutions. Independent monitoring finds

violations of Nestlé weak Instructions.

|

|

|

International

Code and Resolutions

|

Nestlé

Instructions

|

| 1.

Applies to all countries as a minimum standard. |

1.

Apply to a list of developing countries of Nestlé’s

own invention. |

| 2.

Applies to all breastmilk substitutes, including other milk

products, foods and beverages marketed to replace breastmilk. |

2.

Apply only to infant formula and to those follow-up formula

with the same brand name. |

| 3.

No idealising pictures or text in any educational materials. |

3.

Allow for baby pictures “to enhance educational value

of information”. |

| 4.

No promotion to the public or in the health care system, direct

or indirect. |

4.

Allow for company “Mother Books” and “Posters”

with corporate logo to be distributed or displayed by health

workers. |

| 5.

Educational material with corporate logos may only be produced

in response to a request by government and must be approved.

No product names allowed. |

5.

Allow educational materials with corporate logos for use by

health workers in teaching mothers about formula. |

| 6.

No donation of free formula or other breastmilk substitutes

to any part of health care system. |

6.

Allow for free formula if requested in writing by health workers. |

| 7.

There should be no display of brand names, or other names

or logos closely associated with breastmilk substitutes, in

the health care system. |

7.

Allow for wristbands, feeding bottles, health cards etc. with

corporate logo. |

| 8.

Promotion of breastfeeding is the responsibility of health

workers who may not accept financial or material inducements

as this may give rise to conflict of interests. |

8.

Allow for “general” videos, brochures, posters,

breastfeeding booklets, growth charts, etc. No brands but

corporate logo allowed. |

| 9.

Samples only allowed if necessary for professional evaluation

and research. |

9.

Allow samples to introduce new formulas, new formulations

and samples for new doctors. |

| 10.

Sponsorship contributions to health workers must be disclosed. |

10.

On a case by case basis, financial support is allowed (does

not mention disclosure). |

| 11.

Labels must follow preset standards. WHO does not vet or approve

labels. |

11.

Nestlé claims its labels were developed in consultation

with WHO. |

| 12.

It is for governments to implement national measures. Independently

of these, companies are required to ensure compliance with

the International Code at every level of their business. |

12.

Nestlé Market Managers should “encourage”

introduction of national codes [voluntary unenforceable codes

rather than laws]. |

Small victories:

In 1994 the World Health Assembly stated that complementary feeding

should be ‘fostered from about 6 months’ (click

here for Resolution 47.5). It took 9 years of letter writing,

media work, demonstrations and further World Health Assembly Resolutions

before Nestlé said it would change the labels of its complementary

foods to comply (see the codewatch

section for past campaigns and Nestlé responses).

19 years after the

Code, following a television

exposé, Nestlé said it would endeavour to label

products in the correct language.

Time

for a tribunal

Nestlé’s

claims do not stand up to scrutiny and it dislikes having its

case challenged.

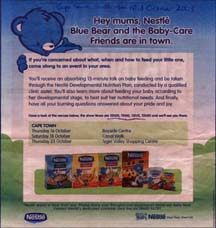

Debates

The company used to

refuse to speak in public meetings if IBFAN members were present.

This changed in 2001 thanks to pressure from the boycott and Nestlé

has taken part in a number of debates with Baby Milk Action in

the UK. Nestlé boasts about its openness to face its critics

in a new leaflet (pictured above), but fails

to mention two things.

Firstly, it continues

in its attempts to speak without Baby Milk Action being present.

Secondly, it does not

acknowledge that it has lost every debate as its claims do not

stand up to the documentary evidence of its own promotional materials

(click

here for a debate report).

European Parliament

The European Parliament

held a public hearing into Nestlé malpractice in November

2000. The IBFAN group from Pakistan, the Network for Consumer

Protection, presented evidence of malpractice. UNICEF’s Legal

Officer was present to respond to any questions regarding interpretation

of the marketing requirements. Nestlé was invited to present

evidence on its marketing policies and practices, but it objected

to the presence of IBFAN and UNICEF and refused to attend. Instead

it sent someone who had been paid to conduct an audit of Nestlé’s

activities in Pakistan. The auditor was unable to respond when UNICEF pointed out that Nestlé’s

Instructions used for the audit are not the same as the Code and

Resolutions (click

here for full details).

Nestlé rejects

public tribunal

Boycott coordinators

have put a plan to Nestlé for ending the boycott (see

Boycott News 29).

The first point requires Nestlé to accept the World Health

Assembly position that the Code and Resolutions are minimum requirements for all countries. Nestlé refuses

to do so.

Campaigners cannot

re-negotiate the marketing requirements with Nestlé - it

is the responsibility of the World Health Assembly to review progress

and address new issues and questions of interpretation. However,

campaigners are calling for Nestlé to attend a public tribunal,

where Nestlé and health experts can present evidence to

an independent panel.

The purpose of the

tribunal is to evaluate who is telling the truth. Nestlé

has rejected this proposal. Individuals and organisations are encouraged to write to Nestlé

asking it to agree to the public tribunal. Write to:

Peter Brabeck-Letmathé

Chief Executive

Nestlé S.A.

Vevey, Switzerland.

Or send a message via

http://www.nestle.com/

A

history of PR disasters

|

Nestlé’s

Chief Executive Officer, Peter Brabeck-Letmathé,

(right) claims that he personally investigates any hint

of a violation of the baby food marketing requirements.

As the man personally responsible he often over-reacts to

criticism of the company, causing Nestlé more problems.

For example,

when the UK Advertising Standards Authority effectively

branded Nestlé ‘a liar ’ (as the marketing

press put it) for claiming to market baby milk ethically,

Mr. Brabeck held a press conference in London and lambasted

company critics, including the Director General of UNICEF.

Stunned journalists then ran headlines such as ‘Mr.

Nestlé gets angry’ (Independent on Sunday,

9th May 1999).

|

|

A more costly example

is when Mr. Brabeck wrote to critics and policy makers around

the world with a hard-bound book containing letters which he claimed

were “official government verification that Nestlé abides by the Code”. Those who read through the 54 letters

found many were no such thing. The company had to apologise as

some of the authors complained their letters had been misrepresented

and used without permission (click

here for further details).

How

you can help

Nestlé spends

as much on marketing and PR in 15 minutes as Baby Milk Action

runs on for a year. We constantly struggle to raise funds to keep

operating. Our small number of staff frequently have to reduce

their hours when funds are short. Can you help to keep us running

by sending a donation, becoming a member or purchasing Baby Milk

Action merchandise? Please

visit the on-line Virtual Shop.

To send letters calling

on Nestlé and other companies to stop malpractice see the

codewatch section. You can

also send messages of support to governments when Nestlé

is lobbying to weaken legislation.

Sign

up to support the boycott. Petitions are presented to Nestlé

from time-to-time. The boycott

section contains suggestions for action.

|